Darby O’Gill and the Little People (1959) movie review

1959’s Darby O’Gill and the Little People is a riot of forced perspective, practical effects, charming performances and authentic Irish folklore. It’s also pure nightmare fuel, traumatizing multiple generations of children with its rotoscoped phantasms.

There’s something so disingenuous about saccharine, ultra-sanitized children’s movies. Were these people never kids? Do they not remember the absolute terrors childhood imaginations are capable of? The bony, taloned hands just waiting to snatch warm ankles from beneath the bad? The moldering hags levitating near closet doors? The sharp-eyed boogeymen just waiting for their moment to steal kids away to an eternity of servitude?

Darby O’Gill and the Little People is a remnant of a former time, when film-makers weren’t afraid to traumatize children in service of wonder. Old, weird, wonderful Disney movies like Darby O’Gill or Bedknobs & Broomsticks end up coming across as genuine fairy tales, works of mythology or folklore, with their blend of darkness and light. They’re also much more in-keeping with the world that children inhabit, in all its wonders and holy terrors.

The Background of Darby O’Gill and the Little People

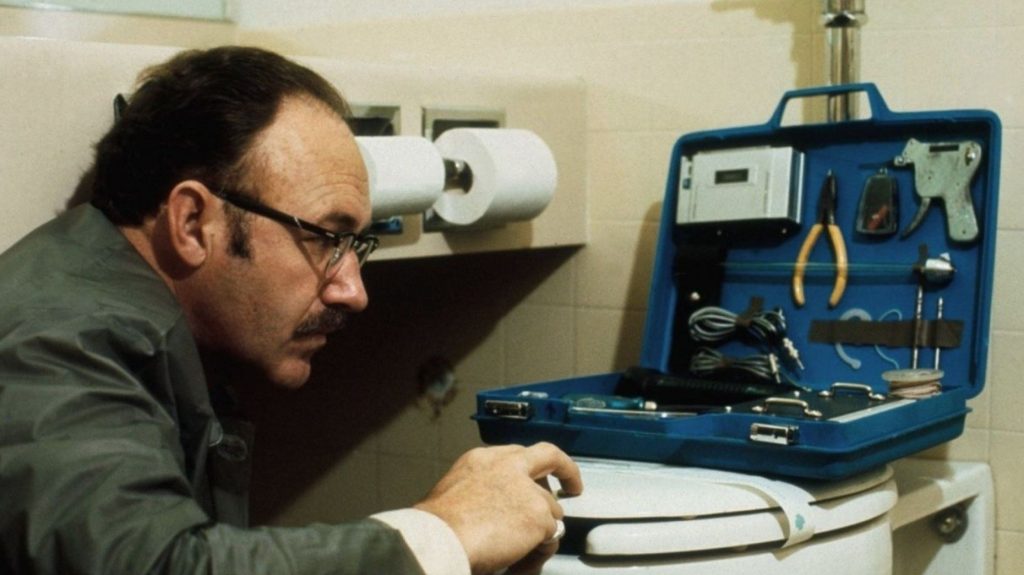

Walt Disney had been wanting to make a film based on Irish folklore for years by the time Darby O’Gill started production. Being half-Irish, Disney had grown up hearing stories of leprechauns, banshee, pooka and death coaches. Disney had started brainstorming a feature about leprechauns as early as 1945, with he and several concept artists traveling to Ireland in 1946 to brainstorm, gather ideas and concept art and collaborate with the Irish Folklore Commission. By 1948, Disney had decided to base his movie on Herminie Templeton Kavanagh’s “Darby O’Gill” books. By 1958, when production on Darby O’Gill began in earnest, they had scrapped the idea of doing an animated feature in favor of live action. Robert Stevenson, fresh off an even more traumatizing stint on Old Yeller and eager to rehabilitate his reputation, was tapped to direct. Talk about a talent for disturbing children’s dreams!

The Plot of Darby O’Gill and the Little People

Darby O’Gill, played by Albert Sharpe, is a caretaker for Lord Fitzpatrick, a wealthy land-owner, living in a house on the grounds with his daughter Katie, played by Janet Munro. Unfortunately, Darby doesn’t spend as much time working as he should, preferring to spend his days down at the pub, entertaining his neighbors with stories of madcap exploits against King Brian, the lord of the leprechauns. This causes Lord Fitzpatrick to deem him beyond his prime, forcing him to bring in a replacement to be the new caretaker, Michael, played by a young and strapping Sean Connery.

One night, Darby’s communicative horse makes a break for it, bolting for the ruins of Knocknasheega – based on The Rock of Dunamase in County Laois, Ireland – rumored to be the home of King Brian and the leprechauns. Darby’s talking horse kicks him down a well, where he finds himself in the Land Under The Hill, where he meets King Brian, in an originally uncredited role from Jimmy O’Dea, for the first time. He’s given fine food and drink and a beautiful violin to play, but he’s told he won’t be able to return to the mortal realm ever again. Darby employs some of his trademarked trickery, playing a reel so fine on his new, beautiful violin it sends the leprechauns into a frenzy, causing them to take to their steeds and head off screaming into the night like a pint-sized Phantom Hunt. Darby makes a break for it, returning to his home to await the inevitable visitation from King Brian.

When he comes, Darby tricks King Brian into staying until the cock crows by playing a game of drinking and rhyming all night long. King Brian loses his powers with the sunrise, allowing Darby to capture him in a burlap sack until he can decide on his three wishes.

More hijinks ensue as Darby and King Brian try to outsmart each other, as King Brian tries to trick Darby into making his wishes, thus freeing him. Things come to a head when Katie learns that Michael has come to replace Darby as the caretaker, causing her to leave the gatehouse, the only home she’s ever known. They get into an argument, during which the talking horse bolts. Katie goes racing after him into a storm, with Darby hot on her heels in pursuit, At the ruins of Knocknasheega, Darby encounters his worst fear – the dread banshee, which he last heard the night Katie’s mother had died. Things get even bleaker still with the cóiste bodhar, the death coach. Once the cóiste bodhar has been dispatched, it can’t return empty handed. Darby finally makes his last wish – to be allowed to take Katie’s place. As he goes spiriting off into the underworld, King Brian joins him for one last trick, conning Darby into making a fourth wish, negating the first three in the process.

In the final moments, both Katie and Darby are spared, no worse for wear and with a fantastic new tale to tell down at the pub.

How Darby O’Gill and the Little People Holds Up

More so than most other films based on folklore, Darby O’Gill and the Little People actually feels like a folk story. Leprechauns being driven into such a frenzy by fiddle playing they go racing off into the night on tiny horses sounds exactly like something you’d hear from an Irish teller of tales. It’s full of passing references to authentic Irish myths, too, which can come and go too fast to catch if you’re not paying attention, like when they compare the talking horse to a pooka, a shapeshifter from Irish folklore. It gives the film a warm, human, lived-in quality that’s refreshing in today’s hyper-produced world of tentpole blockbusters.

There’s some charming music, too, between Darby’s fiddle playing and “Pretty Irish Girl,” a duet between Munro and Conner that would see some legitimate chart success.

It’s entertaining, too, full of light-hearted exploits and adventures like you’d read in a book of fairy tales. Add in some of the spookiest, spectral FX ever burned onto the eyes of children and you’ve got a true gem of an under-appreciated Disney film from a time when they weren’t afraid to go out on a limb and take risks.

Darby O’Gill and the Little People can be streamed on Disney+.

J. Simpson is a prolific academic writer, journalist, and critic, specializing in dark, experimental, and avant-garde art. You can follow him on Letterboxd, Twitter, Instagram, Threads, BlueSky, and GoodReads.