“Phantom of the Opera” (1943): A Lush Technicolor Reimagining of Gothic Horror – Film Review

The 1943 adaptation of “Phantom of the Opera,” directed by Arthur Lubin, stands out in the history of cinema as a lavish interpretation of Gaston Leroux’s classic novel. This version is notable for its transition from the silent film era’s expressionist style to a Technicolor spectacle, merging horror with operatic grandeur.

Reinventing a Classic

Unlike the shadowy, silent terror of the 1925 version starring Lon Chaney, the 1943 “Phantom of the Opera” brings a different flavor to the haunting tale. Claude Rains steps into the role of the tormented and disfigured composer, bringing a more sympathetic, if not tragic, nuance to the character of Erique Claudin. The film shifts focus slightly to emphasize the Phantom’s backstory, his descent into madness, and his unrequited love for the soprano Christine Dubois, played by Susanna Foster.

Technicolor Dreams and Nightmares

One of the most striking aspects of this adaptation is its use of Technicolor. The vibrant hues bring a new dimension to the Paris Opera House, with lavish sets and costumes that provide a stark contrast to the Phantom’s shadowy existence. This visual opulence was a deliberate choice, aimed at captivating the audience and providing a sensory feast that black-and-white films of the era could not achieve.

Artistic Obsession and Isolation

Claudin’s transformation into the Phantom is a metaphor for the isolating effect of artistic obsession. His life, dedicated to music, becomes a lonely path that ultimately consumes him. The film explores how his devotion to art, combined with personal grievances, leads to a destructive isolation, symbolized by his hidden existence beneath the opera house. This thematic exploration raises questions about the cost of artistic perfection and the thin line between passion and obsession.

Romantic Elements and Character Dynamics

The romantic subplot between Christine Dubois and her suitors adds a layer of complexity to the narrative. Unlike many horror films where romance is peripheral, in “Phantom of the Opera,” it is central to the plot and character motivations. Christine’s relationships with Anatole (Nelson Eddy) and Raoul (Edgar Barrier) reflect the contrasting worlds of daylight and darkness, mirroring the dualities within Claudin himself.

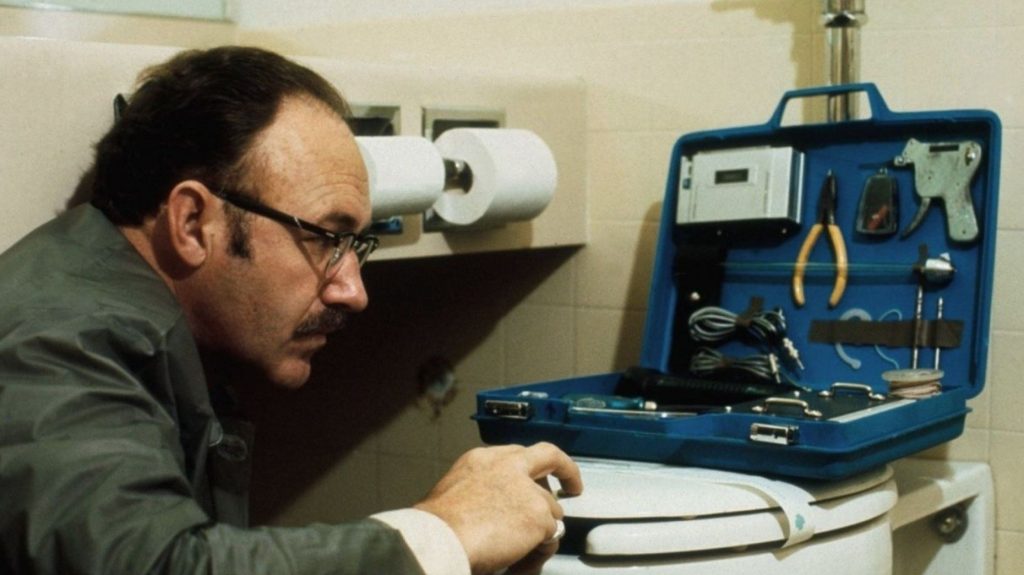

Behind the Mask: Production and Design

The production of the 1943 “Phantom of the Opera” was a grand affair, with Universal Studios sparing no expense to recreate the opulent world of the Paris Opera House. The set design was one of the film’s most significant aspects, with the opera house being meticulously constructed to reflect the grandiosity and scale of its real-life counterpart. The chandelier scene, in particular, became iconic for its technical execution and dramatic impact.

The makeup for the Phantom, while less grotesque than in the 1925 version, required a delicate balance to make Claude Rains’s transformation both believable and pitiable. The makeup artist, Jack Pierce, known for his work on Universal’s classic monsters, created a subtler yet impactful look for the Phantom, aligning with the film’s more romanticized narrative approach.

Musical Heartbeat

Music plays a central role in “Phantom of the Opera,” with the film featuring extended opera sequences that showcase the talents of the cast, particularly Foster as Christine. These performances are not merely decorative but are integral to the film’s narrative, illustrating the Phantom’s obsession with music and Christine’s voice. The score, blending original compositions with classical opera, enriches the film’s emotional and dramatic landscapes.

Performance and Character Depth

Claude Rains delivers a nuanced portrayal of the Phantom, balancing menace with vulnerability. His performance is complemented by the strong cast, including Nelson Eddy as the baritone lead and Edgar Barrier as the police inspector, both vying for Christine’s affection. The dynamic between these characters adds layers to the story, offering a blend of romance, suspense, and tragedy.

While the 1943 “Phantom of the Opera” may lack the macabre intensity of its silent predecessor, it carved its niche as a visually stunning and emotionally rich adaptation. It won two Academy Awards for its art direction and cinematography, testament to its visual and aesthetic achievements.

The film’s influence extends beyond its immediate success, contributing to the evolving narrative and stylistic treatment of the Phantom legend in cinema. It stands as a testament to the power of classic Hollywood to reinterpret and visually amplify well-known stories for new audiences.